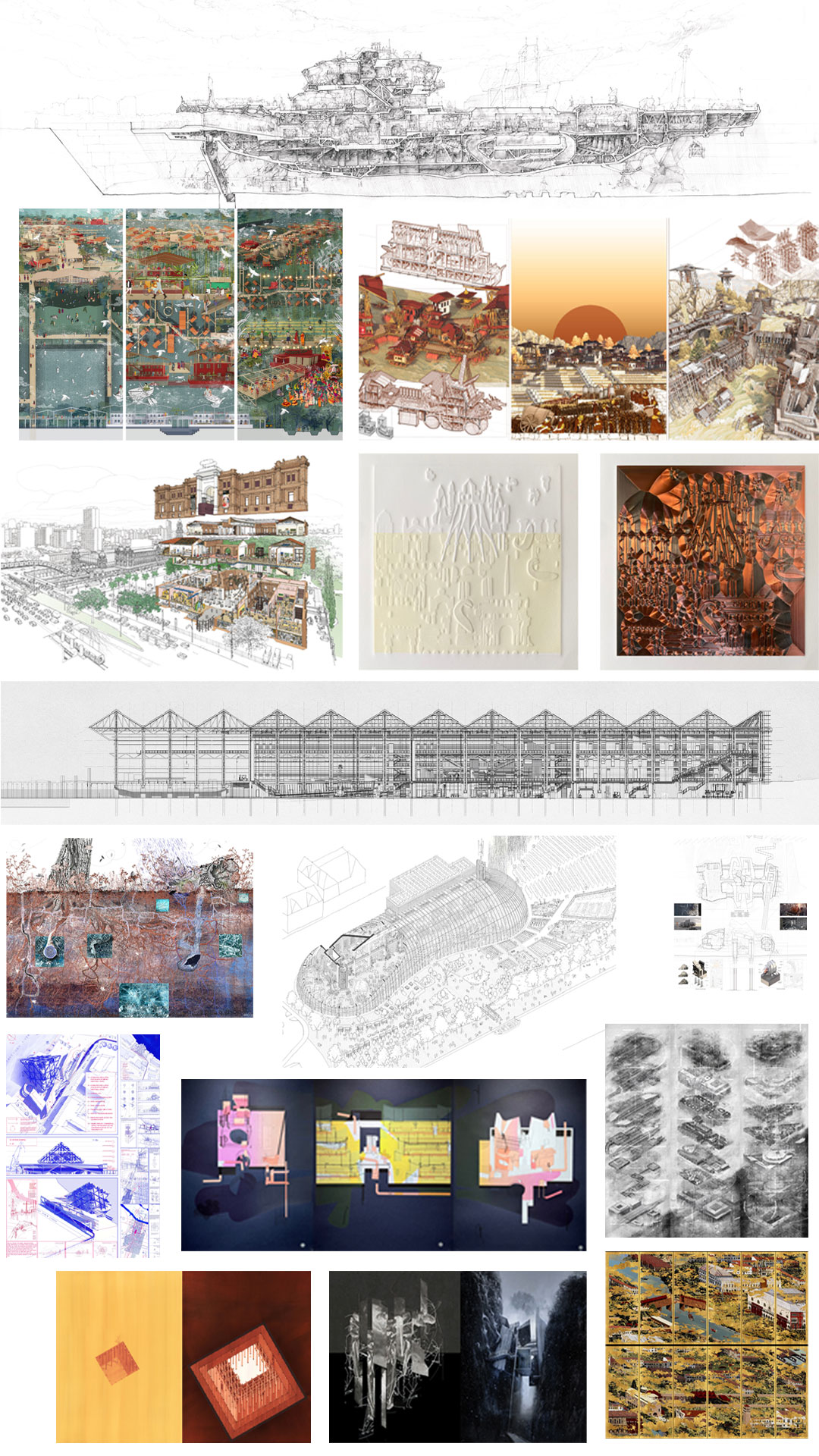

My first acquisition for the Heinz Architectural Center, the Carnegie Museum’s architecture department, was a set of ink sketches by Álvaro Siza Vieira. Like many Siza drawings, these bird’s-eye and worm’s-eye views of the Galician Center of Contemporary Art (CGAC) evoke context and topography. The viewer discerns a spatial designer testing options for the intersection or overlapping of architectural volume.

Siza communicates the process of design in action. This is also apparent in two other sets of acquisitions: hand-drawn plans plus one long working drawing by Peter Salter of his Walmer Yard housing in London and initial sketches by Tezuka Architects of their Fuji Kindergarten in the Tokyo suburbs. With Salter, there is an intimate connection between specific spatial detail and the very act of drawing. With Tezuka, the drawings reveal a synthesis of hand and brain in search of figurative and structural resolution.