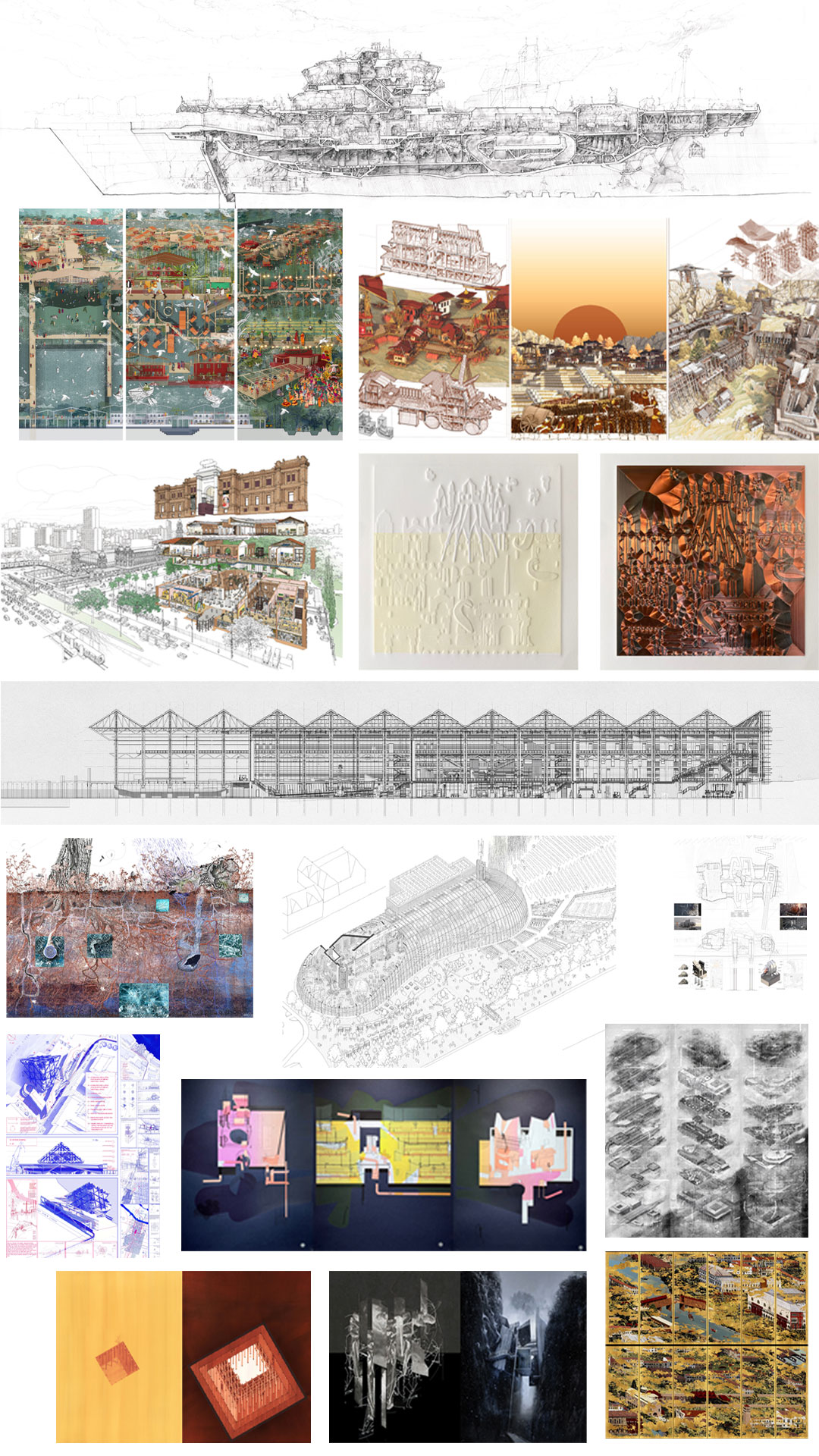

In some ways, what was most intriguing about their presentations about drawing, was the constant discussion of drawing as a performance – for a client, for a design team, for a competition jury. Indeed, what was most interesting was a renewed energy in understanding drawing as a mediative act; after almost a quarter century of photo-realistic CGIs and hard-line drawings, the wavering imperfections of the gesture have been rediscovered for their own value. In the approximate, wavering and bent lines, we read the desire of speculation, the allure of possibility.

This isn’t a casual issue. The tools that have been developed and proliferated into the architectural process were intended to erase the subjectivity of the hand. Sketchup, Rhino and Revit all took their model as the hard-line vectorial style of the pen-and-ink drawing that emphasise geometrical precision. Their designers assume we want to live inside an 18th-century perspective drawing manual. 3D programs have their own kind of tyranny – yes, you avoid the impossible “unbuildable” conditions of the speculative sketch, but you are forced to start in real dimension, full-scale, often resolving geometrical conditions in plan or section before you can begin to see them. The most adept practitioners of these tools see through their cranky preconceptions and sketch in them anyhow, developing personal methods to circumnavigate their crushing literalness, but this is often hard-won and rarer than one would expect. Many more of us just succumb to the rigours of the software developers and let them dictate our work.

Narinder Sagoo of Foster + Partners, in describing a drawing process that can be often collaborative across platforms, between team-members, wasn’t having any of that. Not one to be subject to technology, he talked about the act of drawing as one of story-telling, most importantly one where the pleasures of open-ended nature of the design journey can be savoured as much as the outcome. His cinematic mashups of sketch and paint (with soundtrack!) were powerfully seductive. Dimitris Grozopoulos, with an urban-designers’ eye, was less invested in the gesture and more in the power of the icon to organise spatial identity, turning layers on and off in the same drawing to effortlessly shift the scale and geography of the same image.

Jason Parker, of Make Architects, sought to embrace drawing as a mediating process that through gesture, collage and exploration develops architectural ideas outside of itself. His discussion of drawing was less descriptive of a finished act of seduction and one of the frenzy of communication – can you quickly go from physical model to image through a combination of photoshop-style painting and over-drawing to discover an architectural idea? His was an uncertain search, one of someone who is not quite sure where the journey leads, but one open to the possibility of discovery.

A couple of weeks previously at the Soane Museum, Ken Shuttleworth gave a talk about his ambitions as co-curator of the prize. In recounting a journey into architecture that began with youthful drawing, he took a turn away from a traditional, visual definition of the act as descriptive towards its productivity in the design process – “Drawing is thinking,” he commented. It is a way of exploring a project, testing and speculating on it. When we talk about drawing in aesthetic terms, we lose the sense of it as an exploratory activity. After all, architects are rarely in the business of describing what is there – but what might be.

One can hardly escape the ghost of Soane when one talks of drawing in his house. It was a pleasure to find that the museum has begun to spawn so much new life by engaging with contemporary designers. Over all our shoulders were the array of Joseph Gandy presentation renderings that had clearly helped Soane develop an understanding of architecture that could create atmospheric and spatial effects. But The Architecture Drawing Prize has helped bring the conjunction of those two things into a new kind of presence – to see the continuity of architectural efforts despite the gulf of centuries. With contemporary architectural explorations on the walls opposite their 18th-century ancestors, both reminded us that we can’t forget to explore the past – and the future. Even though we may be disinclined to see the iPad as itself artistically productive, these three invited us to break the preconceptions of software, to try to see what would happen if we followed them through the glass into an architecture that might become…

This post forms part of our series on The Architecture Drawing Prize: an open drawing competition curated by Make, WAF and Sir John Soane’s Museum to highlight the importance of drawing in architecture.