The next generation, including Joseph Connors and Howard Burns, explored new ground, as second generations do. They put drawings centre stage and in so doing caused a historiographical revolution. Buildings, Guido continued, are evidence of the ‘winners’, not just of architectural competitions but of politics and power. Drawings open up more private and forgotten territories, the realm of speculative ideas and individual fantasies, which may give deeper and wider insights into the architectural psyche.

This also raises the issue of what makes a specifically architectural drawing, as opposed to a drawing for any other purpose. Here the discussion turned to Raphael and his letter to Pope Leo X of 1519, which was a plea to preserve Rome’s ancient monuments in the face of papal urban ambitions. Raphael has a reputation as the most confident and serene delineator of the Renaissance – though Waldemar Januszczak detects a thread of “restlessness and experiment” throughout his oeuvre in a Sunday Times review of the Ashmolean Museum exhibition of his drawings. In any event, Raphael is quite clear that “the way of drawing specific to the architect is different from that of the painter.”

Architectural drawings have to give accurate measurements, and are principally plans, sections and elevations. Raphael allows that perspective helps architects to “better imagine the whole building furnished with its ornaments,” but is firm that “this type of drawing . . . is the preserve of the painter.” It took the next generation, and in particular Palladio (who was 11 years old when Raphael wrote his letter), to free architectural drawings completely from perspective and depend entirely on orthogonal projections. The stage was set for the next 400 years of architectural drawing, and the flowering of the Beaux-Arts tradition.

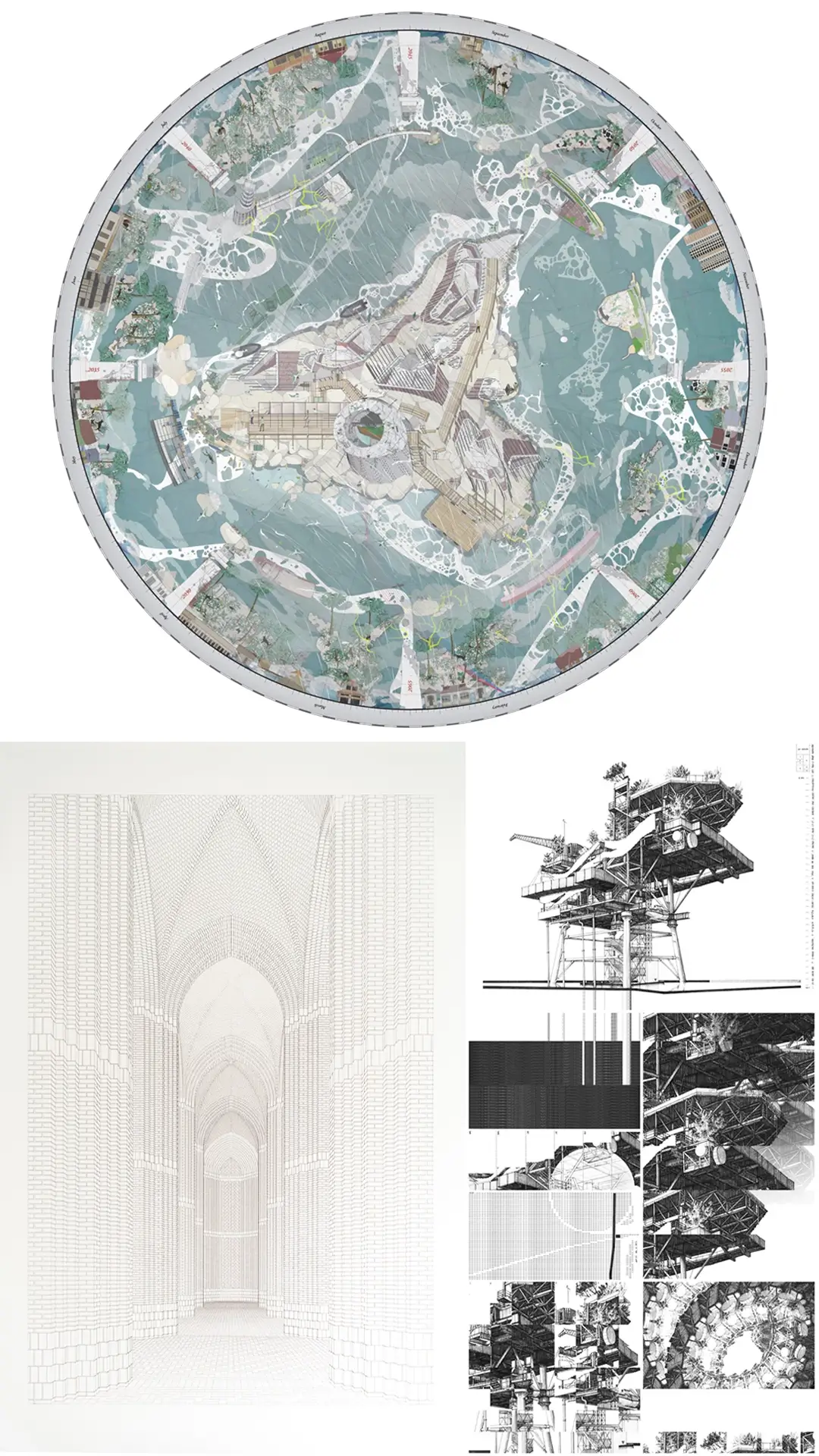

As that tradition has run its course and new digital technologies challenge anew the conventions of architectural drawing, the next generation of architects will no doubt explore the relationship between buildings and ideas still further.

This article forms part of our series on The Architecture Drawing Prize: an open drawing competition curated by Make, WAF and Sir John Soane’s Museum to highlight the importance of drawing in architecture. The article originally appeared in The Architectural Review.