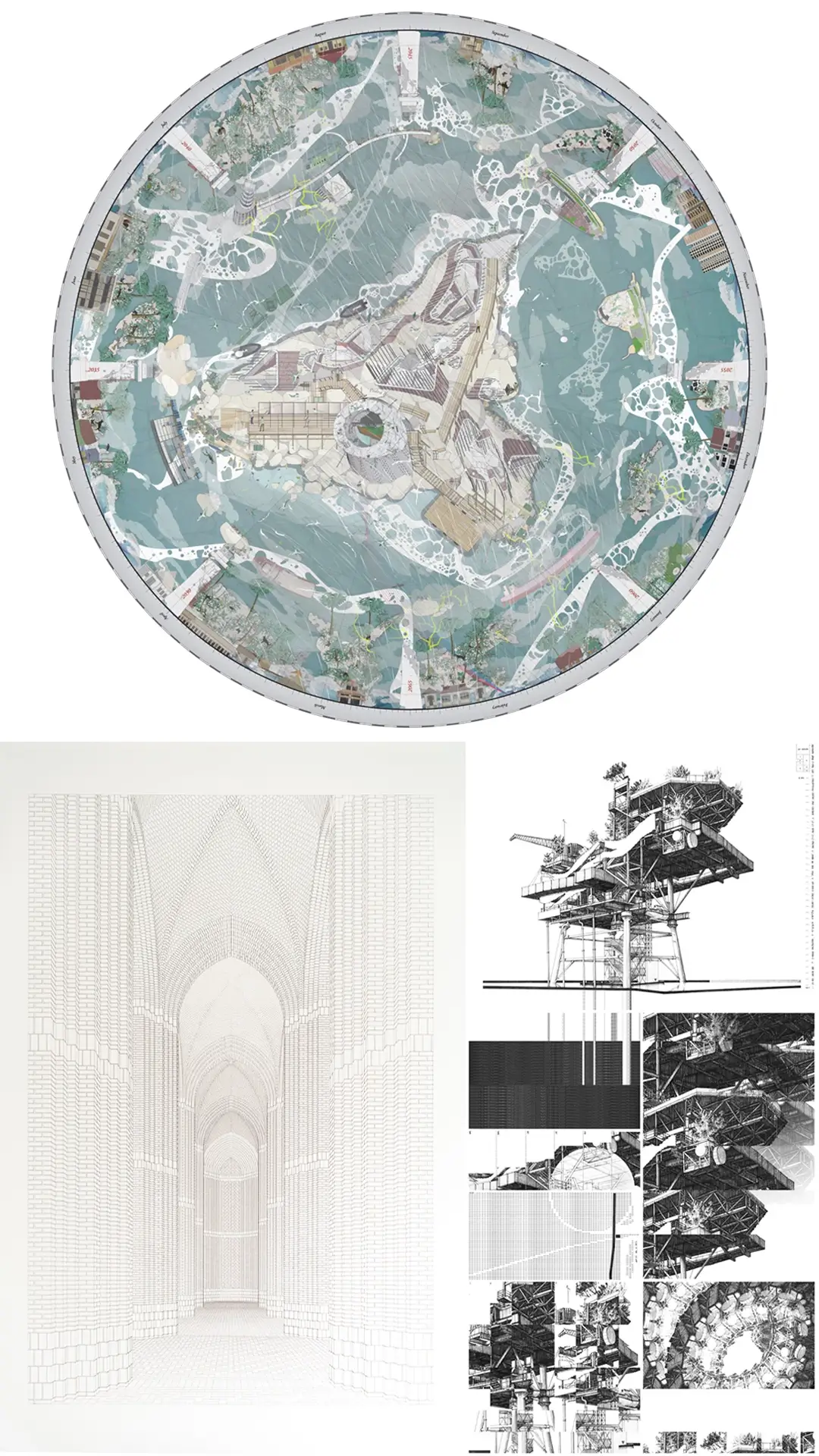

Drawing is hazardous. There is no instant clarity. Drawing forces you to think again, and again. Drawings cannot be finished. Pens, pencils and paper are the primary building materials; sketches are the first intimations of the tense physicality and potential of architecture, and the effect that even the smallest detail may have.

Drawings are marks on what the art historian, John Berger, describes as the “eddies of time”. And he adds: “When the intensity of looking reaches a certain degree, one becomes aware of an equally intense energy coming towards one . . . the encounter of these two energies, their dialogue, does not have the form of a question and answer. It is a ferocious and articulate dialogue.”

To draw in a fertile way is to imagine and substantiate one kind of form, and then realise that you are creating something different and self-challenging. Unlike a CGI, a properly exploratory drawing made by hand can never exude the aura of a virtually completed architectural product.

Deanna Petherbridge, author of The Primacy of Drawing, writes: “One of the purposes of drawing should be to challenge the philosophical and artistic tedium of the readymade. In a sea of tired, second-hand and endlessly recycled images, the indigestible dross that has passed many times through the body politic only to resurface again and again in the sewers of cyberspace, the drawn image that springs from the visual imagination of the individual is infinitely more potent and subversive.”

When Oscar Niemeyer finally put his felt-tip down all those years ago, he asked which of the drawings I liked best. Was this a maestro-supplicant routine? Not at all. He just wanted to find out what the sketches had made me, a stranger, think of. Drawing as democracy.

In The Hollow Men, we read: “Shape without form, shade without colour, / Paralysed force, gesture without motion.” Remind you of anything? I’m sure I heard a mouse-click.

This post forms part of our series on The Architecture Drawing Prize: an open drawing competition curated by Make, WAF and Sir John Soane’s Museum to highlight the importance of drawing in architecture. The winning and shortlisted drawings will be exhibited at Sir John Soane’s Museum 21 February – 14 April 2018.