How do you think digital tools have changed drawing as a way to design buildings?

New generations of architects are using their computers to sketch buildings. This is a much slower and more precise process than drawing by hand, and the computer creates what is essentially a fixed drawing. It’s no longer an exploratory sketch, and we don’t see it as one. This can make an early iteration of a building more definitive than it perhaps should be. Then again, 3D models allow you to have multiple points of view of any particular design. It’s so much faster to visualise the whole with a digital drawing or even a 3D print.

But it’s also valuable to have to draw a section through a building – this doesn’t happen often enough anymore – because it makes you think it through differently. All tools have to be used with a lot of discretion and intelligence. Right now I am excited by the potential of VR (virtual reality). My clients are too. As an industry I think we need to invest more in this to really reap its benefits.

What do you look for in architects applying to Make in terms of draughtsmanship?

We like to see pencil drawings as well as drawings in other media. We really want to see the range of what someone can do. This also applies to the subject matter. Of course we need to see drawings of buildings, but it shows creativity and inspiration if there are other subjects included. Once we received an application that included pressed flowers, which was a good way of communicating awareness and originality.

How do you support drawing at your practice and how should the profession support it?

We have life drawing classes at Make. They’re a great way to encourage our architects to use drawing as a problem-solving tool. When I can’t find a solution to a problem, I often start to draw – it helps to clear the mind and to focus. I think a lot of architects do this, and it should be celebrated.

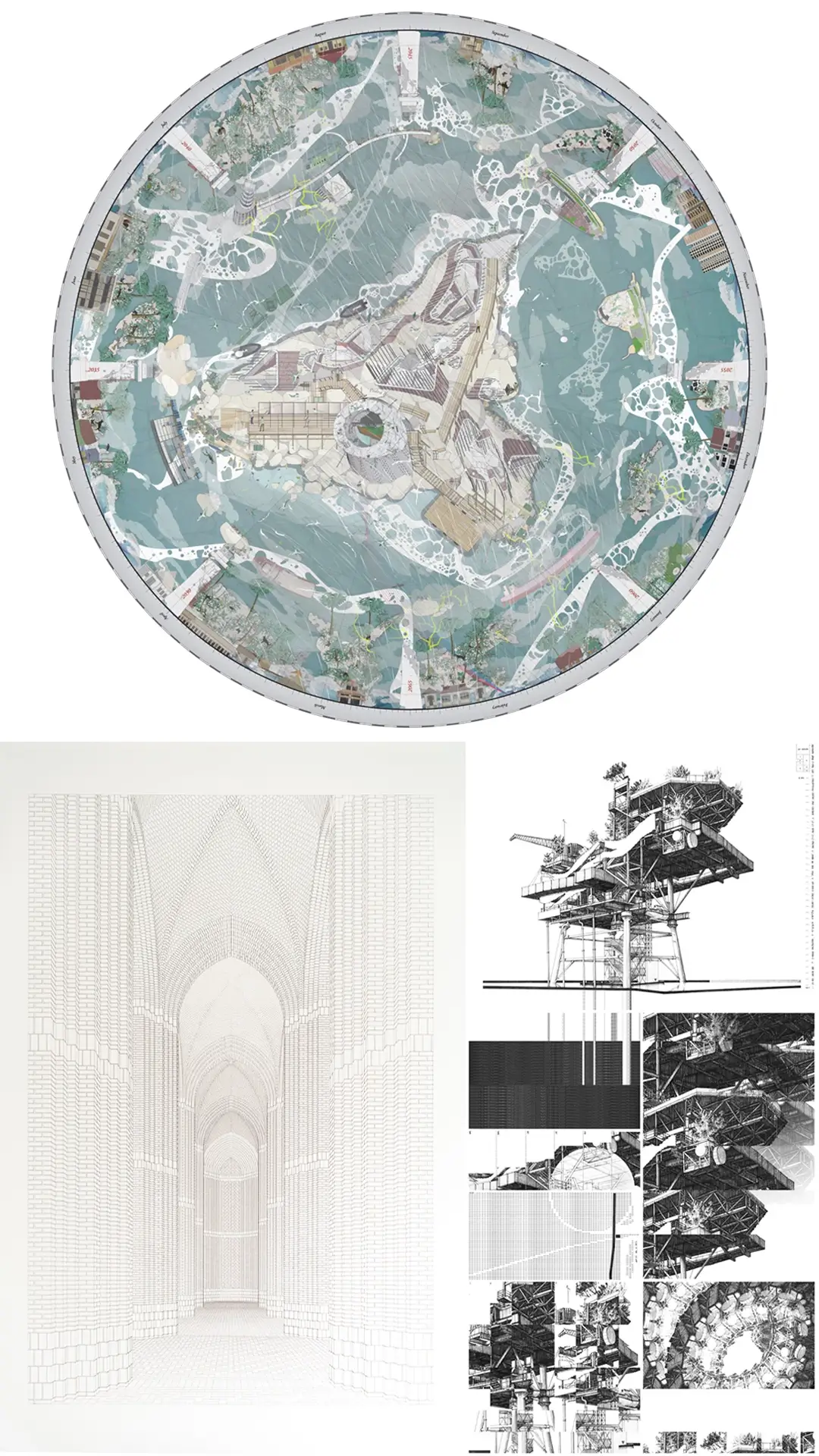

The Architecture Drawing Prize is a fantastic way to promote drawing in the profession and reflect on it as a form of presentation and in the context of masters like Soane, too. I think the profession overall should embrace drawing as a way of telling its story. It’s about the process of designing rather than the final building. In the world of CGIs this often gets forgotten but can be far more interesting. Digital drawing and VR sketching will be amazing tools for the profession, too. No one thing should outweigh another though; each has different uses, each has different benefits, and all should be embraced.

How would you sum up the role of drawing for you as an architect?

Drawing has always been a part of my life, and I basically see it as a way to explore. It’s about curiosity. I worked with Norman Foster for some 30 years. At his practice, drawing was a fundamental part of how we thought about buildings. It was equally as important to me as I set up Make and planned our future. I sketched on theatre programmes and napkins. I still do!

And clients always respond well to sketching. I draw a lot with clients in meetings, translating our discussions pictorially. It’s not as easy for people to type up the minutes, but a picture paints a thousand words.

This interview forms part of our series on The Architecture Drawing Prize: an open drawing competition curated by Make, WAF and Sir John Soane’s Museum to highlight the importance of drawing in architecture.