Climate activists from Impossible Rebellion outside Selfridges in London

The fast pace of the luxury industry still creates huge amounts of waste, particularly with frequent store refurbishments leading to short lifecycles for materials. In a report published by Arup, it is estimated that retail store fit-outs will typically be replaced every 3-8 years, with some temporary pop-up stores and seasonal fit-outs lasting as little as 15 days. To have a truly circular economy, physical stores need to embody the same circularity values as the brands they represent. Rethinking fit-out for disassembly, re-use, and recycling offers significant environmental benefits, demonstrating a clear trajectory to improve the carbon footprint of the retail sector.

While simple in principle, materials re-use requires extra preparation and planning in the early design stages to ensure circularity is embedded in the project vision, rather than added on as a checkbox exercise down the line. Pre-design and demolition site assessments are needed to determine how materials can be reused, whether through recycling, repurposing, repairing or reusing in their current condition. During these assessments, we can identify and record the materials available, and how they’re mounted, to estimate recovery rates and determine the best course of action for each material. Early engagement with craftspeople and suppliers is also needed to ensure that the desired outcome is possible, and to make sure the materials are eligible for re-use later. Finally, storage facilities need to be in place to protect the materials during construction. These early steps are crucial for ensuring maximal materials re-use while alleviating costs and complications.

Gucci is one of the latest luxury brands to introduce a circular fashion initiative

Circularity hierarchy

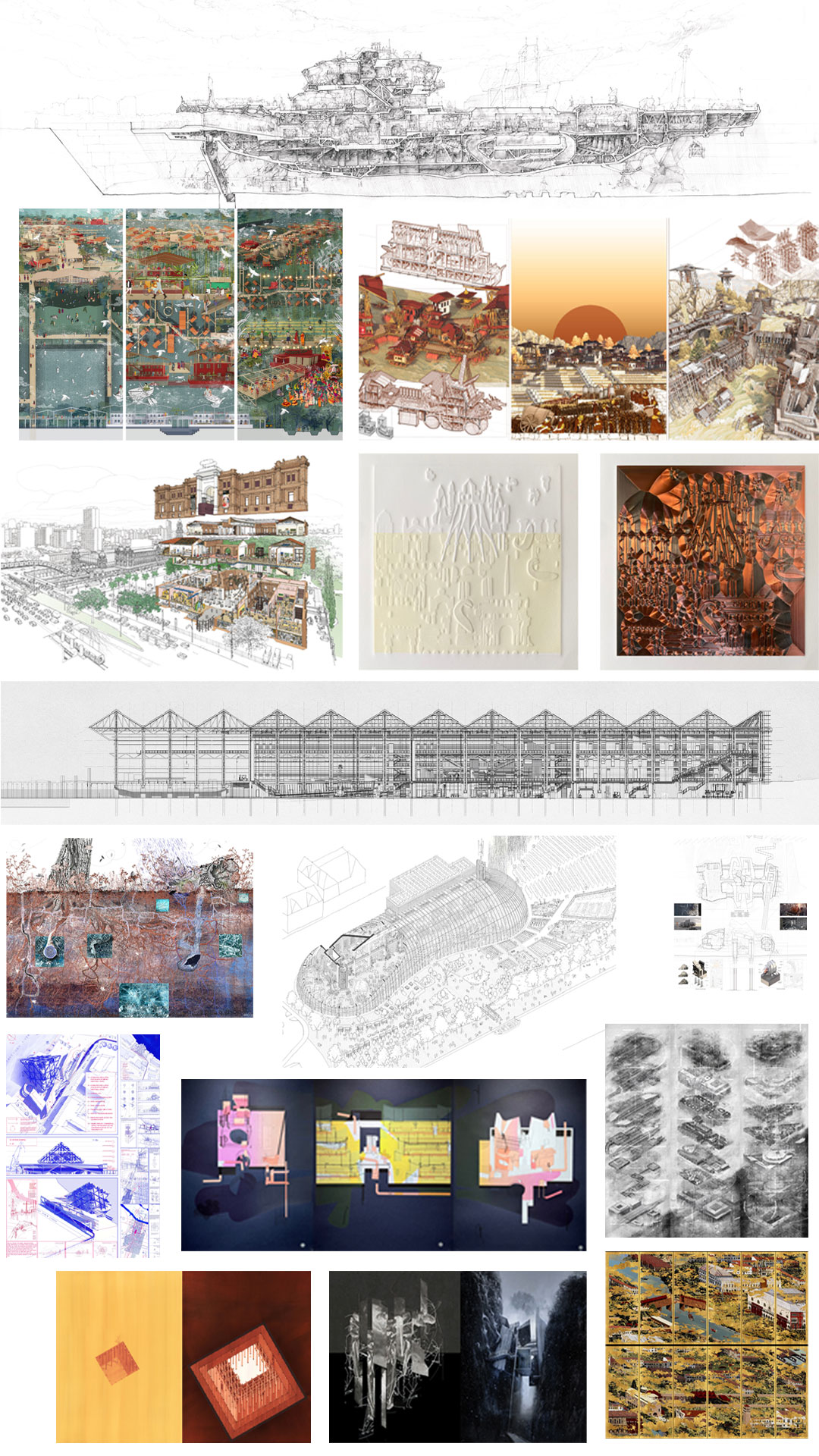

Designing with circularity in mind can make the biggest difference to reduce resource intensity across a material’s lifespan. The diagram below outlines a hierarchy for circularity, defining the possible outcomes for a material over its lifetime – the bigger the orange circle, the greater the amount of energy required to reuse the material.

It’s important to remember that each step in the re-use process requires energy, and this can potentially undermine the energy savings to be gained by choosing re-use in the first place. This means the most efficient form of re-use is to retain a material unaltered and in situ. The next best option is repairing, reshaping or transporting materials to reuse elsewhere on site. While this option also has a carbon cost, it remains lower than recycling. Due to the many step requires in the recycling process, some recycled products have a higher embodied carbon figure than a comparable new product, despite being more ‘circular’.

At Make, we use three key criteria when appraising existing materials to determine where they fall on the circularity hierarchy: re-use potential, demountability and value. These three factors help us identify whether a material can be retained or re-imagined, whether it can be extracted in whole or in parts, and how the carbon saving compares to the financial value of re-use, taking both time and quality implications into account.

Case study: Marble

We recently conducted a materials audit during a feasibility study for a luxury department store, where we assessed materials within a department according to our circularity hierarchy. We identified large quantities of high-quality marble across the space which could be reused while retaining a luxury feel.

In the context of marble slabs, there are various re-use options available across the circularity hierarchy. As a highly durable, long-lasting material, marble will typically outlast retail fit-outs, but the potential for re-use greatly depends on the ease of recovery. For example, threaded mechanical fixings are typically the easiest to remove and offer the greatest potential for circularity. Nails and other friction-based mounting can be removed but may damage materials in the process. Likewise, adhesive layers are highly variable depending on the specific product used during installation, as such they can greatly impede re-use. It may be impossible to remove adhesive-bound materials without breaking them, and some adhesive may remain on the material, limiting its re-use options.

Generally, it’s best to retain materials in the largest size possible, and to keep them as local as possible to reduce transport emissions. Thermal processes such as flaming should also be avoided. Reusing marble in large slabs is highly sustainable, as the material undergoes minimal processing and is preserved for future uses. Large slabs can be used for wall or floor cladding, and curved slabs can be machined flat, or the curve can be integrated into a design. Surface refinishing can also give marble a new look (with minimal wastage) and can often be performed on site.

Marble furniture can be another effective way to re-use large stone slabs in a more mobile and reconfigurable way. Irregular shapes, quantities and sizes which cannot be reused on floors or walls can be remade as bespoke coffee tables or retail plinths. Other materials can also be introduced to change the look and feel of the stone.

Cutting natural stone down to smaller pieces is an irreversible process; however, it vastly opens up the potential for re-use. Smaller pieces can be applied to surfaces as tiles, or they can be mixed and integrated into various parquet and mosaic styles. They can also be repurposed and crafted into decorative objects and displays.

Every option for re-use has a carbon trade-off, but by reframing luxury stores as a library of materials, we can intertwine sustainability and quality. Brands can harness their physical stores to demonstrate their commitment to the circular economy and set the agenda not only for fashion design but retail design as well.