Owen Hopkins, Senior Curator of Sir John Soane’s Museum and one of the prize’s jurors, says that at a fundamental level drawing is ‘about holding an instrument and making a mark on a surface’. The charity, Campaign for Drawing, of which I used to be a trustee, got around the difficulty of definitions by describing drawing as ‘marks with meaning’. Such catch-all descriptions aim to combine inclusivity with a celebration of skill, but it is important that definitions don’t stray so far from traditional concepts of drawing so as to render the concept meaningless.

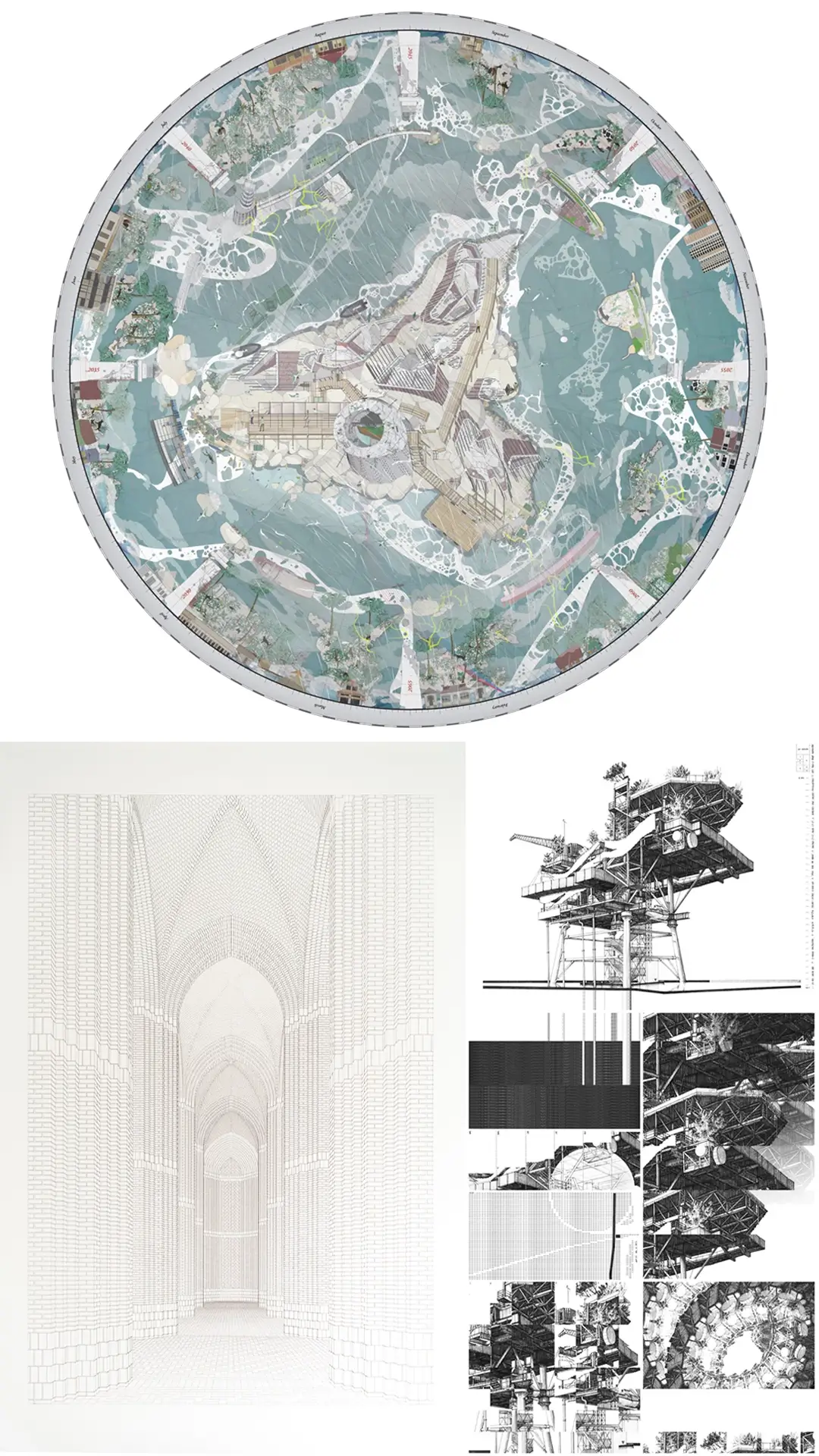

The development of digital drawing in recent decades has dramatically shifted our conception of drawing and the type of skill entailed. This year’s overall winner was Anton Markus Pasing with a mind-boggling work ‘City in a box: paradox memories’. Pasing, who also won the digital category, describes his method as ‘asking questions or telling simple stories’. His anything but simple, sci-fi inspired image is an interior on steroids – a view of chaos that is reminiscent of a city that has grown beyond anyone’s control.

New developments in drawing techniques have not just altered our ability to depict complexity, but have created a desire for greater complexity or an idea that we can make a visual description of an irrational world without understanding it. This is a fundamental shift from an era where drawing expressed simplicity and rationality, through the clarity of geometry or the simplicity and beauty of a line.

Even the hand drawn entries on display at the Soane revel in being complicated. Louis Sullivan’s ‘Ark City’, for example, depicts an enormous vessel, floating through an imaginary flooded London. Drawn in pencil by a group of friends over several weekends, the ark, is a gargantuan machine, a Mad Max of the oceans.

The winner of the hand-drawn category presents complexity of a different kind. Architect Anna Heringer submitted an embroidery, depicting the masterplan of Rudrapur village in Bangladesh where she has been working since the 1997. Hand sewn on a blanket made from recycled saris, the work was created by a group of women working at Dipdii Textiles, a collective Heringer helped to establish to strengthen the local economy of the village.

The work is exquisite and highly skilled, combining the sensibility of the artisans with the original lines drawn by the architect. But should embroidery be considered a drawing? According to Hopkins, “A line sewn in thread has a tone that reflects the pressure, lightness and intensity of hand-drawing”. Heringer says about her collaborative ”sewn line”, ”It’s a tool of communication with the western world, to show how it’s possible to care for resources.”

The Architecture Drawing Prize raises questions about the meaning of drawing that tackle not only the more familiar ’digital versus traditional tools debate’, but that of introducing new art forms, like embroidery, into the realm of what is defined as drawing. I would welcome an event that debates the merits of broadening the more readily understood definition of drawing with widening its interpretation. In being catholic do we lose something in terms of preserving the skill of draughtsmanship – the very skill the Prize is setting out to preserve – or might we gain a new insight into the scope and breadth of how drawing can be used to present ideas creatively?

This post forms part of our series on The Architecture Drawing Prize: an open drawing competition curated by Make, WAF and Sir John Soane’s Museum to highlight the importance of drawing in architecture. The winning and shortlisted entries for 2019 have been announced and will be on display at Sir John Soane’s Museum until the 16th February 2020.